The Jist: When James " Rhodey " Rhodes was a lower-middle class black boy growing up in South Philidelphia, expectations for what he'd grow up to be were low. But as an adult, Rhodey's been a decorated US Military hero, the private pilot and bestest boyfriend of Tony Stark, a substitute Iron Man for years, and eventually his own armored hero as War Machine. Now, rebuilt with cybernetic parts after being blown up on a mission, he's a literal machine. And as his name suggests, he wants to declare war-- in this case, on every petty warmonger on the planet.

The Crew: Greg Pak ( writer ), Leonardo Manco ( artist Vol. 1 and issue 8 ), Wellington Alves, Mahmud A. Asrar, Allan Jefferson, R.B. Silva, and more( artists vol. 2 )

The Verdict: To start with, I want to say that War Machine's redesign for this series may be the least inspired costume design I've seen yet. Not the worst, mind you, but the least original and unique-- it's basically a greyscale Iron Man with an assload of weapons hanging off his back. Which is the most exact description you can give of War Machine's looks, but I would have liked to see a bit more thought than " Iron Man with attached 90's style armament porn ". He looks like a robotic version of Big Shot, the Punisher spoof from the Tick cartoon who carried a huge box of guns on his back and fired at anything until he ran out of bullets, in which he'd start sobbing about how his mother didn't love him. Re: A SPOOF character, not appropriate for a comic that takes itself seriously.

Of course, there are a lot of things I would have liked to see from this series that I didn't. That description of Leonardo Manco's War Machine design describes how I feel about the book in general-- it's not_that_bad as a whole, but it's definitely an underperformer, especcially given the quality of the creative team.

The central problem with this comic is that it's trying for a balance of real-world commentary and Marvel Universe exploration, and doing it in a very sloppy fashion. This is most obvious in the first trade, where Rhodey takes his cyborganized body to several Marvel Universe third-world military juntas to kill all the " real " bad guys. I'm not terribly opposed to seeing guys who torture and kill innocent civilians getting a bullet in the head, but these are a shamelessly superficial rendition of real-world despots. " Santo Marco " is not Columbia; it's the country Marvel writers use when they want to say something about Columbia ( or other South American nation torn apart by civil war ) but don't want to bother researching the complexities of real-world Columbian politics. So they bring in Santo Marco with its endless supply of two-bit genocidal thugs, and have Rhodey try to solve the country's problems by killing every person with a " kill number " ( something that his cyborg operating system attaches to everyone he sees, based on how many deaths they've willfully caused ).

If you're wondering how flying in to cap warlords in the head is a heroic action ( or even one with any long-term benefit; is the word " power vacuum " even in Rhodey's databanks? ), it's not. Greg Pak has called his approach to this series " Iron Man meets the Punisher ", but he's still playing Rhodey as a sympathetic character, one who is trying to do the right thing, even justifying it by talking about how his cybernetic brain won't let him even temporarily forget every murder and rape he's witnessed. Except that the Punisher isn't a sympathetic character, and especially since Garth Ennis got to him, he's been portrayed as a monster who happens to point his bullets at other monsters. Ennis' stories with the character, especially the ones where he was involved in real-world struggles ( most notably the Irish civil struggles of Ennis' own background ), never suggested that Frank's solution was the right one or even a right one.

Also worth noting about Ennis' real-world commentaries in the Punisher is that he didn't bring in other Marvel characters to make them-- his Frank Castle existed in an independent space, and whenever superheroes wandered in, they were embarrassingly ill-equipped to deal with it. Rhodey, on the other hand, is dealing with military juntas, tribal genocides, and frequent rapes in the Marvel Universe. In Santo Marco, one tribe uses a hacked Sentinel to genetically weed out and kill members of the other tribes. In Aquiria ( a.k.a Marvel's ersatz Middle Eastern theocracy ), he's fighting a private military contractor named " Eaglestar " using appropriated tech from the alien robot Ultimo. And in the opening strip from Marvel's website, Rhodey fights a Roxxon ( a.k.a. Marvel's ersatz corrupt oil conglomerate ) executive trying to eliminate Inuit tribes from ideal drilling space with cyborg bears. Pak wisely knows to have occasional asides from the characters where they recognize how absurd this shit is, but we're still getting world politics shoe-horned into the Marvel Universe in a manner that can't be taken seriously-- and when you have open acknowledgement that one of the female characters was beaten and raped by prison guards, following with a dramatic entrance by Ares, Greek God of War, seems horribly inappropriate.

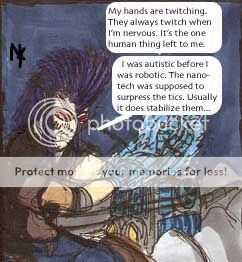

If I seem overly upset with this comic, I have to admit that part of it is because I really like Jim Rhodes as a character, and think that everything I like about him is absent here. When Rhodey debuted as Tony Stark's best friend, he was a perfect and immediate fit because he offered an intrinsically human counterpart to Tony's ubermensch futurism; he was Wilson to Tony's House, down to the unfortunate enabling of Tony' addiction. As the substitute Iron Man and even as the ( unfortunately named ) War Machine, he was a likable character, because he was a hero as a soldier long before he met Tony, and wearing Iron Man armor was a right that he genuinely earned. His conflicts came from the fact that he was deeply uncomfortable with making the kinds of hard moral decisions that Tony has to make on a regular basis-- but all of that's absent here. He can't appear in regular human settings because he's a disfigured cyborg, but if you're wondering how much his condition lowers his quality of life ( and from the looks of it, his new body has all the " armament " of a Ken Doll ), we don't get any answers. All we know is that he's ugly, he's mad, and he's taking it out on everyone his databanks give a kill number. Quite the character reduction.

To the War Machine creative team's credit, the book improves dramatically with the second and final collection, when Rhodey sets his sights on Norman Osborn and his Dark Reign. It doesn't become great, mind you, but it develops the makings for an enjoyable mid-tier superhero book. The supporting cast is expanded on, bringing a " Team War Machine " together from various Iron Man supporting characters, including Rhodey's mother. The opposition is shifted from one-dimensional takes on real world monsters to Norman, and while it's hard to ever believe that the substitute Iron Man is going to be the one out of all the heroes to take Norman down, the guy's scenery-chewing brand of theatrical villainy is always entertaining. And while the art team shifts from Leonardo Manco to various fill-in pencillers and inkers, that actually works to the book's benefit. Manco's dark, gritty style was great when he was working with Andy Diggle on the urban fantasy Hellblazer, but his more realistic rendering only served to illuminate how ridiculous the stories were. The more conventional superhero art the later teams offered played well to the series' tone.

But as they said about J. Edgar Hoover's attentions to the economy-- too little, too late. The book's first arc was an obnoxious throwback to the worst parts of 1990's comics*, and readers picked up on that. It's luck that let War Machine last a whole year, and even with the character getting a big push thanks to Iron Man 2, it may be a while before Rhodey gets another solo series. On the plus side, Pak started the series by showing that Tony Stark had cloned Rhodey a fresh body, and ends it by transferring Rhodey's mind there. No longer a scowling, trigger-happy eunuch, War Machine is in a position where a new creative team can do something really good with him.

While there are some merits to the series and it picks up in the second half, overall it was a failed experiment that left a bad taste in my mouth, so I'll have to give it a Not Recommended.